A Sherpa’s Legacy

Ashwyn k -

Welcome back once again, readers! This time, I’ll finally be talking more about my EBC trek, how interviewing the guide and porter went (spoiler alert: not very well), and more!

After a good night’s sleep in Ramechhap, we headed out at 6:00 in the morning, without breakfast, to go to the airport. Our flight was scheduled for 7:00, but since there were flights from the previous day that didn’t take off, our flight was more likely to depart at around 8:00. Well, that’s what we thought would happen, but we didn’t make it to our destination, Lukla, until 6:00 PM. Due to some big fires a couple of weeks prior and lots of air pollution in Kathmandu, a lot of smoke and fog built up in the valley where Ramechhap is located. Although some flights were able to slip through, since the airport is so small and only three planes can fly at a time, the number of people waiting for their flights just kept racking up as time went on.

By the time it reached 2 PM, we had to make a decision. We were next in line to go on our flight to Lukla, but the weather was unfavorable for any landings. We were offered to fly to the Phaphlu Airport and then take a helicopter from there straight to Lukla, and after another hour of waiting and heavy consideration, we took them up on the offer. It was pricey, but that decision saved my Senior Project.

Because of that helicopter flight, we landed at 6 PM and were able to quickly eat dinner and trek to our first location, Phakding. Had we not made that flight, we would’ve needed to cut our acclimatization day in Namche, which turned out to be the most useful day for what I intended to research, but I’ll get into that in a second. On the way to Phakding, since it was so late, we needed to use headlamps to make sure that we didn’t trip on stray rocks or lose footing and accidentally fall. At this time, I told our guide what I wanted to research and learn more about while we were on our 12-day trek, and he was very happy to help out in whatever way he could! We had some small talk, and after 2 or 3 hours, we made it to our inn, ate dinner, and then went to our room.

The beds were comfy enough for me to get a good night’s sleep, but when I tried to shower before clocking out for the night, I was convinced for 5 minutes that there was no hot water to shower in. Now you might be thinking that I’m complaining about something that should’ve been obvious, but it was honestly a big deal. I had my hopes up since I was told there’d be hot water, and who wouldn’t be stoked! When I turned the dial and didn’t feel anything remotely warm, I became very disappointed, but after leaving the water on for a minute or so, the hot water finally came, and I was happy once more.

The following day, we woke up at 7:00, ate breakfast at 7:30, and were out to go to Namche by 8:00. This trek took us around 6 hours, including our lunch break, but this trek was one of the most visually beautiful of the 12 days. Throughout the entirety of the trek, we could hear, feel, and see a large river that ran through the entire valley up until Namche. I heard countless birds and saw countless horses and dogs. It felt like the opening sequence to a National Geographic documentary, the way it was so beautiful. In all honesty, my favorite thing to do was crossing the bridges that would connect one side of the river to the other. It was thrilling to walk across as they wobbled slightly from one side to another. It felt better knowing that they were very sturdy bridges, so no matter how they wobbled, I could be sure I wouldn’t be greeting death anytime soon.

While we were walking, I realized that if I wanted to interview our guide I would need to wait until we got to our inn, because managing listening to someone in Nepali, while hiking uphill, while filming it, and making sure to not fall off all at the same time, is not very easy. So, I brought it up to our guide, whose name is Mahendra, and asked when would work best. He said once we get to the hotel and he gets free time, we can, so I agreed and we kept cruising through our trek.

What I didn’t see coming, however, was that our guide didn’t know too much about ecotourism. Mahendra has only 1 year of experience being a guide, because before this, he was a porter for 8 years doing Annapurna Base Camp. As a guide, he hasn’t been trained or educated much in the effects of tourism, so I wasn’t able to ask him much at all… Luckily, on our 2nd day in Namche, we visited both the Everest Museum and Sagarmatha Next. Although I wasn’t aware of these places before my trek, the two buildings were abundant with information on the transformation of Nepal into a tourist country and the changes that local organizations are making to combat mass pollution on Everest.

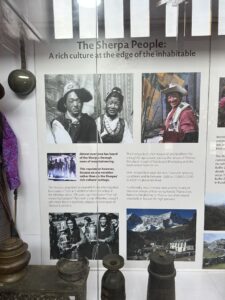

In the Everest Museum, I learned more about the lifestyle changes of the Sherpa people following the switch to tourism in the 1950s. The Sherpa (“sher-pa” meaning “east people”) people originally migrated from Tibet and settled down into the uninhabited valleys of the Himalayas around 500 years ago. They rapidly adapted to the harsh conditions of the Himalayan valley and set up three committees to manage agriculture and grazing, forest use, and cultural life. Sherpa culture is heavy on the sustainable use of natural sources, such as forests in a rule set called “Dhi,” which also helps to regulate cutting of grass, digging of potatoes, and movement of livestock. Although they were able to survive, they weren’t able to fully thrive due to the cold climate limiting their harvests to only once per year. In the mid-1800s, the Nepali government allowed only Sherpas to go through the Nangpa La pass, which opened up a connection straight to Tibet. This allowed many families to profit from trade, but not everyone was able to. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many Sherpas migrated to the British-ruled Darjeeling in search of employment as laborers. In 1907, the British realized the endurance that the Sherpas innately had, and when Nepal finally opened its Himalayan borders to foreigners in the early 1950s, the British immediately capitalized on the new opportunity and paid Sherpas to guide them through the mountains. Many Sherpas who work as porters live successful lives, while Sherpas who don’t have a family member in the business tend to remain in poverty, often seeking out better lives by migrating to other places abroad.

Sources for my information:

As we know, in 1953, Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and British mountaineer Edmund Hillary successfully summited Everest, marking the first time in known human history that any man had reached the highest point on Earth. The influence of both Norgay and Hillary became apparent within the first year after their ascent. Mountaineers from all over the world flooded in with the hopes and dreams of achieving what the two heroes achieved. The word “sherpa” holds respect in modern day due to this massive event. Sherpas are world-renowned for their endurance and their ability to maneuver and guide people through the most dangerous terrains ever discovered. To tourists, mountaineers, and everyday folk, the Sherpa people and their legacy are honored and respected. In Nepali and Indian schools, the first summitting of Everest is taught heroically. The famous photo of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay holding up his hand as he celebrated their success at reaching the top is considered one of the most important photos in human history, proving the true strength of humankind.

Despite this major feat, there are arguments that the business has taken a wrong turn. As more people take an interest in summiting Everest and other mountains in the Himalayan range, there will be a correlation in a rise of pollution and environmental destruction. One of the assistant Sherpas in the 1953 trek, Kancha Sherpa, stated, “The snow-capped mountains are not as snowy, and I fear their essence and beauty are slowly diminishing.” As his grandson says, the glaciers of the Himalayas are the water towers of the world. They feed and grow millions of people, yet rapid climate change is changing the normal melt-freeze cycle of the glaciers.

On August 16, 2024, the rapid outburst of two glacial lakes caused major damage to a village downstream, named Thame. This disaster wiped out homes, displaced families, and destroyed farmland that many relied on for their livelihoods. It was a stark reminder of how vulnerable these communities are to the effects of climate change, and how the growing impact on the mountains doesn’t just stay in the mountains — it spills into the lives of the people who have called this region home for generations.

Sagarmatha Next, founded in 2019, was created to help solve some of the other problems that tourism has brought to the Everest region. Their main mission is to promote sustainable tourism and protect the natural beauty of the Himalayas for future generations by focusing on physical pollution, such as littered trash and recycling. As more and more trekkers and climbers visit the area, trash has started piling up on the trails and mountainsides, and Sagarmatha Next is trying to change that. They launched a project called Carry Me Back, where tourists can help by carrying small amounts of waste back down to Lukla as they return from EBC. They can pick up a 1kg Carry Me Back bag from either Pangboche or Namche as they descend back to their intended location, and the idea is that 1kg is convenient enough that most people can carry the extra weight without much struggle. It allows for easy, convenient, and efficient waste control. The goal is that if 80,000 people can each take 1 Carry Me Back, a majority of the waste on Everest will be cleared out!

They also invite artists from around the world to create art out of the trash they collect, such as the national bird, a grasping hand made out of tents, and more. They collect bottle caps from all water and soda bottles since they are unable to be recycled normally and they melt them down into small miniature models of the Himalayan region surrounding Everest.

Sagarmatha Next is taking a major step towards sustainable tourism, and I truly believe that if anyone can make a change, it’s them.

That’s all for this blog post, until next time, readers!

Comments:

All viewpoints are welcome but profane, threatening, disrespectful, or harassing comments will not be tolerated and are subject to moderation up to, and including, full deletion.