Week 4: Smaller Bubbles – It’s a Game, So Play It

Hey guys Welcome back!

Survey responses are rolling in as more and more coaches, athletes, trainers, and their relatives are answering questions.

Last week, we talked about the importance of fundamentals and how the understanding of them separates elite athletes from mediocre athletes. This week, we’ll dive into how a deep understanding of the fundamentals affects the brain of athletes both in training and competition.

In Chris Bailey’s book Hyperfocus, one of the core ideas is the idea of the human attention span.

According to Bailey, our attention span contains “our entire conscious world” (Bailey 28). It can be represented by a finite bubble, meaning we can only fit so many things inside of this bubble at once. Certain tasks take up varying amounts of space depending on how experienced the individual is at a certain task. Think back to the first time you started driving. You were trying to be super careful when you were pulling your mom’s car out of the driveway, taking the utmost care of every movement that you did, making sure that you didn’t hit anything or damage your mom’s car. When you finally get on the road, you probably were going only 60 miles an hour on the highway in the right lane, letting others pass you because you didn’t want to hit anybody. As you gained experience, driving became a lot easier and you can do a lot more things while driving, like changing the song, pushing the speed limit, having a conversation, or eating a hamburger. In sports, when an athlete is learning a fundamental movement or trying to correct a movement in training, he or she must fill his or her attention span with a singular complex task.

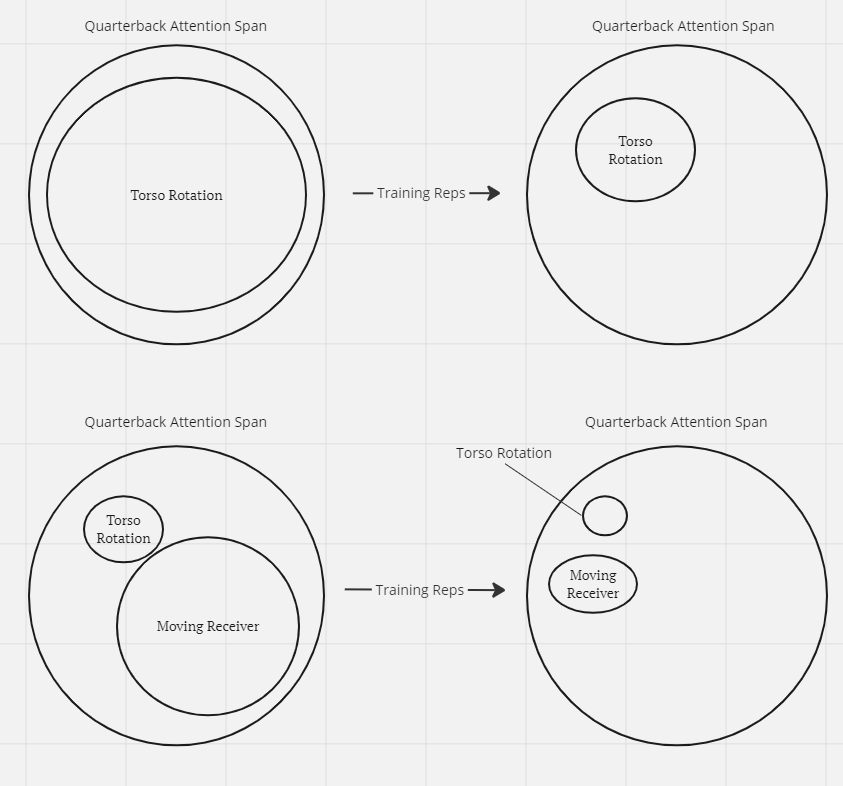

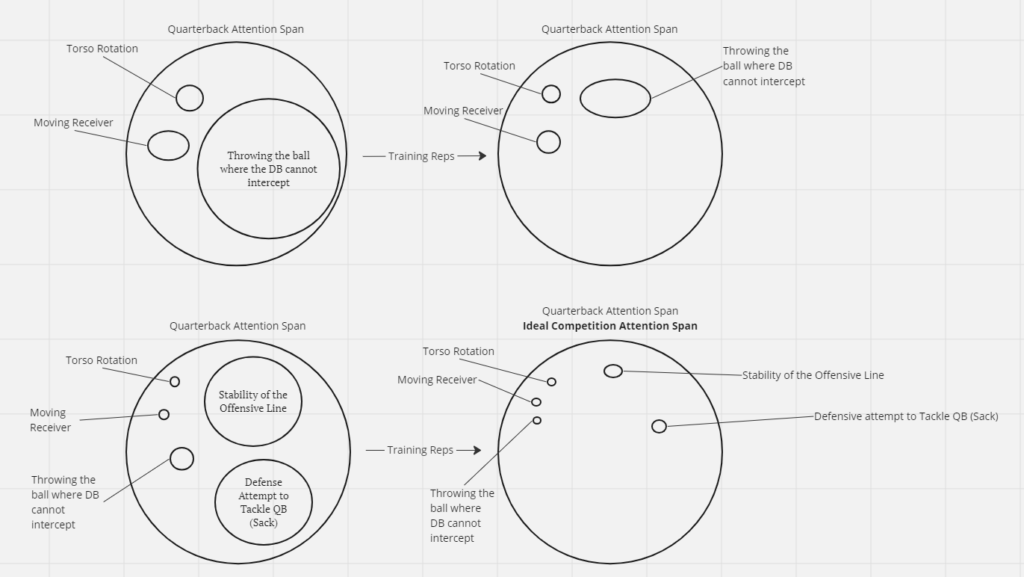

Take a football quarterback for example. Let’s say that this quarterback struggles with his torso rotation throughout his throwing motion. In training, there are times when he must solely focus on his torso rotation, sometimes just throwing to a stationary target. By doing this type of training, the quarterback fills his attention span with the task of throwing the ball while focusing on torso rotation. When the quarterback becomes more familiar with the new motion, the task of only focusing on rotating his torso takes up less space in this attention span. He can then start to practice with a receiver on a specified route, as he focuses on throwing to a spot, as well as adapting to his receiver’s movements and speed. When both the receiver and quarterback execute more successful pass completions in practice, they can now start to add a DB (defensive back) to guard the receiver to simulate the pressure of the QB throwing accurately. After that, you put the offensive line and the defense in the play, simulating the real game in “game speed” by adding pressure through the defense attempting to tackle the QB (Sack), or making the QB improvise the play if something goes wrong.

With each task that we add to the football player’s training, the previous task took less space in his mind than when he just started that same task. When a new task presents itself, it takes most of our attention span, and we try to break it down and learn it using our brain’s prefrontal cortex where most of the problem-solving happens. When we fill our attention span with one singular task, we want to be detailed in knowing why we do a movement. When we are hyper-analytical of our actions, we use left brain thinking, analyzing the position of every move and the reasons behind it. (Nilsson et. Al.).

When we become more experienced at a task, it takes up less of our attention span. Our hippocampus moves the behavior or task from short-term to long-term memory (Web MD). When the task is stored in long-term memory, the performance of the task becomes less mechanically demanding and more instinctual and feeling-based. When we base our actions on instincts, intuition, and feeling, we engage our right brain thinking, being more subjective with what a movement is supposed to feel like and when the movements are supposed to happen

Playing the Actual Game

When you enter the competition, it becomes more than just being in tune with your mechanics.

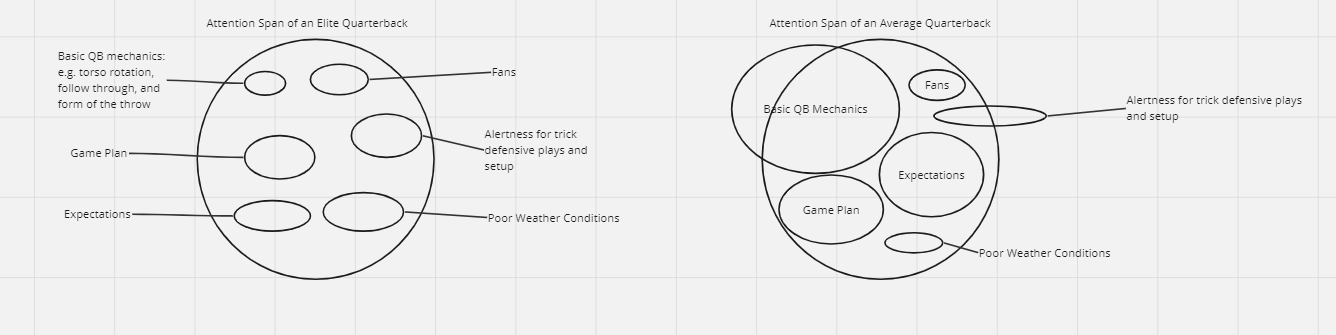

As stated in the last blog, elite athletes have an understanding of the fundamentals down to a science. However, although their understanding of the fundamentals is immensely deep and detailed, in competition, the fundamentals are only a tiny part of their attention span.

The rest of their attention span is left open to other things that are essential to the actual playing of the game.

As a quarterback, the objective is to not just throw the ball and make the receiver catch it, the goal is to score more than the other team, whether that be by field goals or touchdowns. If every receiver is covered by a DB (defensive back), a quarterback can have the most perfect throwing form, and still not be able to win games because he keeps throwing incomplete passes and interceptions, ceding the ball to the opposing team. A great quarterback knows that if his receivers are covered, the best course of action is to run the ball himself. But if his fundamental task of throwing takes up all his attention span, he wouldn’t have been able to make that decision, especially in the heat of the moment. Information starts to get lost as the attention span overflows with mentally demanding tasks. A quarterback may know that he needs to run the ball, but he may not do it because that part of basic mechanics isn’t currently in his attention span.

There are also negative environmental factors that an athlete has to leave attention space for. For example, they can’t control how hostile the crowd is in an away game. They can’t control the fact that the sun is in their eyes. They can’t control how awful the stadium, course, ring, or court is. But they have to deal with it and not let it affect their performance.

For average athletes, variables in competition can drastically affect their performance if they are not adequately prepared. If the task of applying and remembering the fundamentals is too large when you add other factors like the crowd, anxiety, or a poor quality venue, the fundamental parts of an athlete’s game can be pushed out of the attention span as the athlete suffers from “attention overload” as shown below.

Knowing this information, we can deduce how we can improve an athlete’s performance in training and competition on a surface level.

Training should involve filling an athlete’s attention span with a singular fundamental yet complex task. This allows an athlete to be analytical with his or her movements and correct what needs to be corrected without any stakes. By being analytical, the athlete engages his or her left brain thinking, while shrinking the amount of space that that particular task takes up in an athlete’s attention span.

By taking less attentional space, the athlete now can contend with other factors in competition, such as strategy, opponents, expectations, fans, etc. In competition, the athlete relies more on right-brain thinking, the instinctual and intuitive part of the brain, recalling actions that have been stored in long-term memory. Allowing the athlete to perform at their best.

Good QBs (quarterbacks) may throw the ball well; great QBs throw the ball well when a 300lb DE (defensive end) is rushing them. Good basketball shooters may have an excellent shot form; great shooters can get off a shot and make it in triple overtime in the NBA finals. Good golfers may have a good swing; great golfers sink putts when four million dollars are on the line.

Good athletes may have good movements; great athletes play the game.