Week 6 – RSA Implementation

Aadit R -

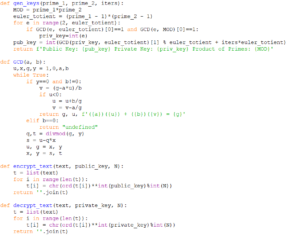

So this week I wrote an implementation of RSA to encrypt a string. Now, the code is probably not the best (optimizations most certainly can be made), but it works, so here it is anyway:

Quick note, the GCD (greatest common divisor) function was not my own, but rather taken from an algorithm written in pseudocode in one of the exercises in Springer’s textbook (Exercise 1.12 to be precise), which I then took and implemented in Python. The algorithm is an efficient way to compute the values for the extended euclidean algorithm (essentially meaning that it returns both the greatest common divisor (gcd) of two integers (a, b) and the linear combination to find the gcd (i.e. the function returns u, v, and gcd(a,b) for the equation au + bv = gcd(a,b)). The gen_keys function was self-implemented (probably the reason why the algorithm is extremely inefficient), following the general process behind RSA.

Now, to use this RSA implementation, we start by generating the private and public keys using the gen_keys function and inputting two distinct prime numbers along with another random integer (for generating a public key that would be more difficult to figure out with brute force).

So, for example, let’s use the prime numbers 107 and 127, and the integer 2 to generate our public and private keys:

Using the public key (40067) and the product of the two prime numbers (13589), we can now encrypt a text message (say “Hello World!”) with the encrypt_text function, which results in the string:

Then to decrypt the message, we can use the text generated (“ข\u05c8ⲺⲺ⢦Ӻᰑ⢦㋁ⲺぎẐ”), the private key (13355), and the product of the two prime numbers (13589) with the decrypt_text function to get the result:

This results in completing our encryption and decryption of the message “Hello World!” using RSA.

Now I could explain exactly how the algorithm works, but given that these blogs have taken long enough, I’ll end by providing a nonmathematical explanation for RSA (and asymmetric encryption in general) instead.

Let’s say there are three individuals (Alice, Bob, and Eve), and Alice wants to send a message to Bob without Eve seeing what Alice has written. Well, one way which Alice could deliver that message so that only Bob can access it is by having Bob buy a safe with a thin slit—which would only allow paper to be inserted and could not be used to take things out of nor see what is in the safe—as well as a key to the safe (which only Bob would hold). Then Alice could write the message and slide it into the safe, ensuring that Bob and only Bob could unlock it and see what was written.

In the context of RSA, the safe would be the algorithm, the key to that safe would be the private key generated, and the slit would then be the public key. Of course, this is a massive oversimplification, but it gets the idea across. Also, this explanation was not my own (not creative enough to think of something like this) but rather one provided in Springer’s book.

Anyways, that’s RSA. My implementation is not what I will be using when testing the different encryption algorithms (there are Python libraries that allow the use of various encryption algorithms, which will provide better baselines to compare them). Also, my code is extremely inefficient when using really large prime numbers (I know that it’s bad and am well acquainted with it’s deficiencies) and doesn’t work exceeding a certain amount (given that Unicode has a limit to the number of characters), but the point of implementation was to better understand the algorithm.

Anyways that’s a wrap for this week. Next week will most likely involve testing out the Python libraries and reading some more of the research papers (along with the textbook, which I still haven’t finished). Thanks for reading all this (if you did), and I’ll keep you updated next week.