Week 4: Why am I sad or happy (when listening to music)?

Welcome back to my blog!

Today’s spring-break edition (comment-cult exclusive) will cover a topic that is at least tangentially related to what filled the last, very ordinary post, which you could briefly and somewhat rudely summarize as the “melodic proclivities of geriatrics,” for which I provided the explanation that more important than the assumed form of musical delivery is ultimately the summoned emotion, a conclusion drawing heavy inspiration from that one proverb about the books and some unfashionable covers.

The next logical question for me had to do with this gap centered between the pure, categorical fundaments of music (scales, chords, as mystical as a dental chart) to “summoned emotion.” Some unifying feature must tinge a song sad, or happy, or other emotive words, or those experiences that words can’t quite touch.

Major (happy) and minor (sad) scales are not the only sort of scales. With the same mercilessness that negative integers are introduced in the 6th grade, or prior if you attend a school that offers senior projects, I share with you that there are many, many more scales, as many as there are negative numbers. Most are not in common use, or in other words, sound rather terrible.

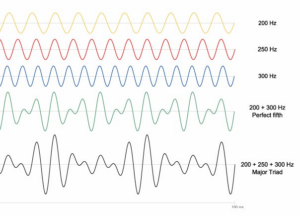

Songs of a certain emotion aren’t so just because of their designated scale(s). As in, minor scales can sound happier, or the opposite. “Take on Me” and “The Sound of Silence” occupy the same minor key center, but only one encourages a positive outlook on life inside my vital spirit. Generally speaking, which is hard to do, minor scales and chords are more dissonant, more acoustically rough, or euphonically challenged. This mounts “tension,” which desires a “resolution,” where the dissonance gives way to consonance in a gratifying release. Consistent with what I can understand of physics, music offers some abstraction of steady (resolved) and excited (tense) states. So, it makes sense to extrapolate human emotions to these visceral, indescribable states, happiness and sadness, respectively.

Minor is also more chromatic, meaning its composite notes are closer together and thus more dissonant. And then one thing leads to another, the ear leads to your brain, and sadness colonizes your brain.

Anyway, back to the retirement-home surveys; the elderly preferred happy, upbeat music. Based on the last 3 paragraphs to the top of this one, what structure contributes to these emotions? Consonance, major, non-chromatic (aka. diatonic). If any of these terms even grazed the thinking centers of your brain, then just know I consider you very intelligent, which is just as well because negative numbers probably entered your wordily purview before 6th grade. Another clue lies in the word “upbeat,” which suggests a faster tempo. This quality wicks movement into your feet and life into your eyes or wherever is hiring, something I can imagine sometimes otherwise lacking in the isolation of a retirement home.

No small number of audience members also attested to the relaxing effects of music, especially within classical music. I think the most important traits for this label are slow tempos and predictable melodic patterns. Tempo and solidity/predictability can be likened to the many bodily functions that pulse in your body and that also happen to keep you from being dead—of course including such highlights as heart rate, blood pressure, or respiration rate. A slower tempo can be physiologically linked to slower pulse rates (but not too slow, obviously), which is associated with calmness.

Thanks for reading!

Comments:

All viewpoints are welcome but profane, threatening, disrespectful, or harassing comments will not be tolerated and are subject to moderation up to, and including, full deletion.